The Library of Juggling

Overview

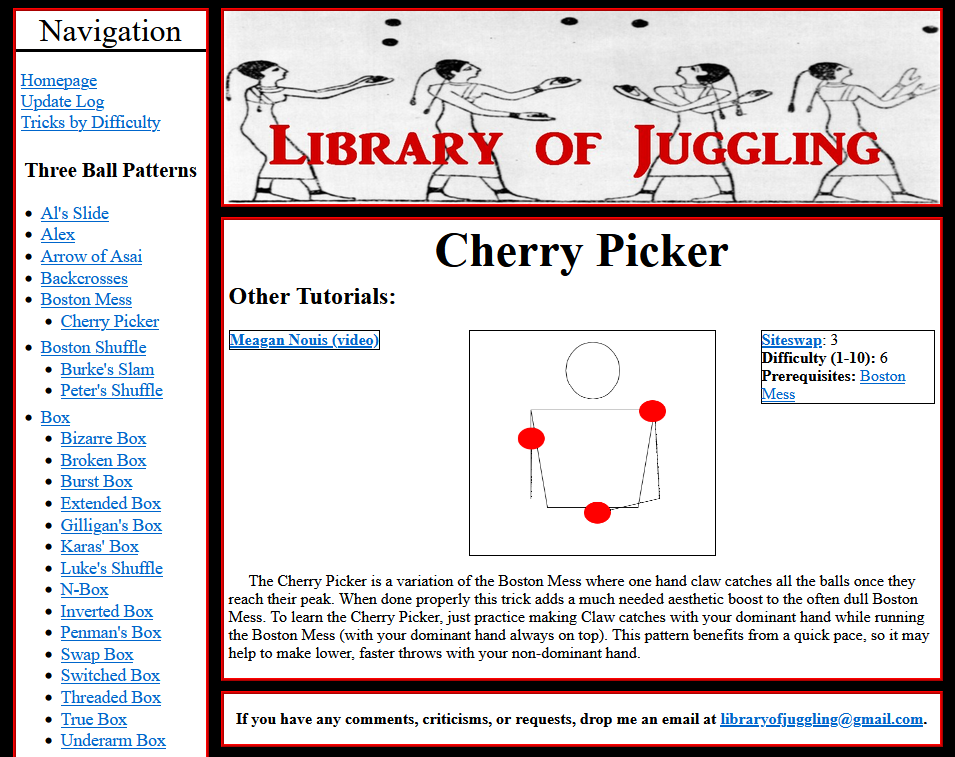

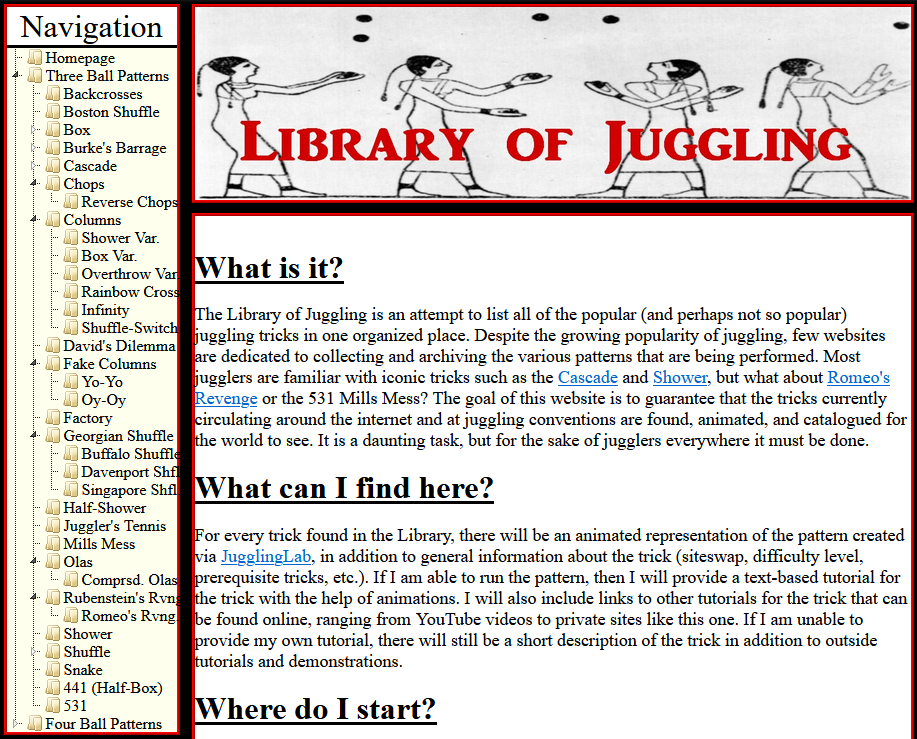

The Library of Juggling is a website that I created in early 2012 to catalog the wide variety of juggling tricks that were scattered across YouTube videos, message boards, and websites. It contains descriptions and step-by-step tutorials for 174 different patterns, with a focus on three-ball juggling. Each trick is shown using an animation created with JugglingLab, which is a piece of software that allows you to render a custom juggling pattern by controlling the position and timing of each throw/catch. These animations are also interspersed throughout the tutorial sections in order to help readers visualize different steps in the learning process.

Since its inception, the Library of Juggling has become a go-to resource for jugglers of all levels, whether they are learning basic patterns like the Cascade or diabolical ones like the Inverted Shower. Unfortunately, I had to stop working on the website in 2015, so it sat in stasis for over eight years before I finally came back and provided a more reliable hosting setup. As part of this migration, I rebuilt the site using Jekyll and cleaned up some of the more egregious HTML code, but the original structure and aesthetic were left intact. All of the underlying data and resources for the site can now be found in its GitHub repository.

In the sections below, I go into more detail about the origins of the Library of Juggling and how it has evolved over time.

The Early Years

I can’t quite remember when I started learning to juggle, but it was probably in late 2010. My early props were scrounged up from whatever I had lying around, from rubber bouncy balls to wooden eggs. Eventually, I got one of those cheap juggling sets and began to practice with more regularity. The idea for a “library of juggling” came to me in late 2011, inspired by the now-defunct KingsCascade1 website. That site had used animations from JugglingLab to create tutorials for around sixty different tricks, and included some fairly obscure patterns that were difficult to find anywhere else. While KingsCascade seemed to be foremost a personal website for its creator Matt Mangham, I intended for the Library of Juggling to serve as an anonymous repository for as many juggling tricks as I could find.

This was all happening early on in my juggling career2, so I planned to essentially learn a trick, add it to the site, then learn another trick, add it to the site, and so on. This naturally led to me specializing in three-ball juggling, since almost all of the cool, named tricks were done using three balls. Progress was a bit slow at first, but by the start of 2013 I had written tutorials for 57 different tricks. One thing that has helped set the Library of Juggling apart was that I broke down the tricks into a set of digestible pieces, often starting from simple one-ball and two-ball exercises before working up to the full pattern. Each of these steps was paired with an animation that provided a visual demonstration of the exercise, which made the text much easier to understand and follow.

Given that the evolution of the site mirrored my personal development as a juggler, it is interesting to browse through older versions of the site on the Wayback Machine3 and see what is effectively a snapshot of my abilities almost a decade ago. My unorthodox progression was already evident at this stage, where I apparently knew the obscure Olas pattern before the simple 423 (I’m skeptical that this is actually true, but it’s an amusing possibility). Looking at these site captures, it’s also rather striking just how quickly everything came together. The website was in its infancy in early 2013, and then mostly complete by the middle of 2014. By that point I had begun to exhaust the existing base of online juggling tutorials, and was increasingly adding tricks that had not previously been explained by anyone in a permanent or accessible medium.

The Middle Years

I began attending college in 2014, and this naturally led to me (reluctantly) prioritizing other work over the Library of Juggling. I still kept at it though, and added several more tricks to the site in my freshman and sophomore years. These included patterns that had languished on more obscure sites, as well as tricks that had recently been invented by well-known jugglers on YouTube. I even hosted a few tutorials submitted by another juggler, Andrew Olson, who was (and is) an incredible inventor of three-ball patterns. The most significant changes to the site, however, were a pair of improvements to its navigation interface.

One of the first design choices that I grappled with when creating the Library of Juggling was how to display its collection of patterns. I wanted all of them to be easily accessible from any page on the site, so I decided to create a navigation sidebar to house the links. My plan was for the list of tricks to be organized based on the number of balls that were needed to perform the pattern, with each sublist being collapsible in order to save space. While modern-day me could have easily written a bit of JavaScript code to achieve the desired effect, high-school me barely knew anything about programming and instead opted to use an existing library called jsTree. Now I don’t think that there is anything inherently wrong with this library, but it was big and slow relative to what I actually needed it to do, and the particular tree that I implemented was just kind of ugly.

In late 2014, a man by the name of Jon4 reached out to me with a rather exasperated email. He wrote, in colorful detail, about how using jsTree (in the way that I had, at least) was an absolutely awful decision, and did far more harm than good. It was quite an entertaining message, opening with the following lines:

It’s no good.

I can’t take it any longer.

I’ve put up with it for as long as I can but I feel our relationship is at a crisis point & I have to put it to you as an ultimatum:

Either that javascript menu goes or I go.

Needless to say, it was the JavaScript menu that ultimately went. Jon was even kind enough to provide me with a simple bit of CSS code to make the plain-text replacement look somewhat decent, code which remains in some form within the site’s source to this very day.

The second significant addition I made to the Library of Juggling during its middle years was the “Tricks by Difficulty” page. When first designing the site, I needed to decide what kind of information should be included for each trick. Aside from obvious things like the pattern’s name and siteswap, I also wanted to provide some indication of how challenging the trick was to learn. What I ultimately came up with was a numerical value from 1-10 that would denote the difficulty of the pattern in ascending order5. Amusingly, I never gave a value of 1 to any trick, so the lowest difficulty level on the site is 2. I was also never willing to give a trick the maximum value of 10, for fear that someday I would come across something that was even more challenging. These quirks point toward a fundamental shortcoming of my approach, which is that the difficulty of every juggling pattern cannot possibly be compared along a single axis.

Nevertheless, the values were a quick and dirty way to sort the Library of Juggling into a set of tiers that could be used to guide a newbie juggler, which was good enough for me. It was also apparently good enough for many of the site’s visitors, as one of the top requests that I received was to add a page that listed every pattern in order of difficulty. Despite this pleading, I always told myself that I would “do it later”. I honestly can’t recall why I thought it would be so hard to add this page, but ultimately it wouldn’t matter because in October of 2014 I received an email from a literal twelve-year-old who kindly provided me with the organized list6. And the rest, as they say, was history.

The Twilight Years

In late 2014, I had a unicycling accident7 and hurt my wrist. At first it seemed like the injury would heal, but after juggling for any sustained amount of time I would inevitably experience sharp pain in my joint. Not wanting to exacerbate things any further, I simply stopped juggling. There was still a backlog of tutorials for me finish, so I was able to put out a final pair of updates in December of 2014 and June of 2015, but that was it. For the next eight years I basically abandoned the Library of Juggling, despite the ever-present text on its homepage promising frequent updates.

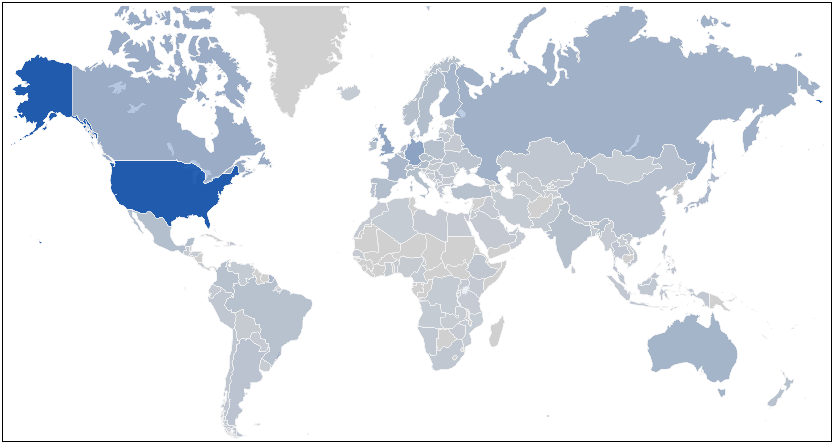

In all that time, however, no other resource emerged to truly replace the site, and it remained one of the largest and most thorough collections of three-ball juggling patterns on the internet. According to an old Statcounter plugin that I used, the Library of Juggling continued to receive over 1000 page views a day, from around 500-700 unique visitors. Perhaps the very existence of the site discouraged others from making their own, as they would simply be duplicating the large amount of effort that I had already spent. Based on some retrospective reseach, it seems that a website called Skilldex.org may have arisen in 2019 as a possible replacement for the Library of Juggling, boasting a huge catalog of patterns with video demonstrations. I write “may have” because the site no longer exists, and the archived version on the Wayback Machine appears to be completely broken. I’m frankly kind of baffled that the combined efforts of the juggling community haven’t been able to outdo a single teenager with some time on his hands, but here we are.

In around September of 2023, I resolved to do a bit more work on the Library of Juggling. I wouldn’t be changing any of the site’s content, but I wanted to ensure that it would remain accessible for the foreseeable future. Back in 2012, I chose to host the site and domain on iPage, whose services and reputation have deteriorated severely over the subsequent decade. Nowadays there are countless companies that provide more services than iPage while also being substantially cheaper. My first move was to take the libraryofjuggling.com domain name (probably my most valuable asset given its recognition and search engine history) and transfer it to Cloudflare. To serve the content of the site, which is made up entirely of static files, I decided to host out of a GCP bucket. This is an extremely cheap option, but a major downside is that requests can only be made over HTTP, not HTTPS8. To address this, I followed advice from DevOps Directive and set up a reverse proxy through Cloudflare. Requests to the Library of Juggling are sent first to the Cloudflare proxy servers over HTTPS, which in turn make requests to GCP over HTTP (all for less than $1 per month).

With the hosting situation stabilized, my second goal was to clean up the Library of Juggling’s HTML/CSS code. This wasn’t necessary to bolster the longevity of the site, but it would make any future updates easier to deploy. Plus the state underlying code was just kind of offensive. I chose to rebuild the site using Jekyll, which relies on the Liquid templating language to generate HTML code out of smaller, reusable building blocks. In my case, this meant that the code for the navigation bar, top banner, and footer could be separated from the page content, with any changes being automatically propagated across all pages9. It also meant that I could create pages using very concise Liquid code, such as the following for the “Tricks by Difficulty” page:

<h1 id="difficultytitle">Tricks By Difficulty</h1>

{%- for diff in (2..9) -%}

<p class="level">Level {{ diff }}</p>

<ul>

{%- assign filteredTricks = site.data.tricks | where: "difficulty", diff | sort: "name" -%}

{%- for trick in filteredTricks -%}

<li class="difficultytricks">

<a href="{{ trick.url | prepend: "/" | relativize_url }}">

{{ trick.name }}

</a></li>

{%- endfor -%}

</ul>

{%- endfor -%}On the CSS side, I really just needed to consolidate styles that had been applied to redundant elements. It was important to me that the appearance of the website not change, so I did careful side-by-side comparisons for each change in the CSS code. Ultimately there ended up being a few small differences, but only the most obsessive of users would be able to notice. One major exception was a yellow-ish background on the navigation bar, which had come from the CSS code that I got from Jon. It was intended to match the background of the original jsTree widget, but I incorporated the code in a half-assed manner that left some parts of the navigation bar with a white background and other parts with that yellow background. In the end, I simply chose to go with the white background, presumably to the delight of anyone with an even marginally aesthetic eye.

And that’s pretty much it. After rendering the new page files, I copied them into the GCP bucket and modified the domain’s DNS records to point away from iPage’s servers. The Library of Juggling is now hosted using the services of two very reliable companies at only a fraction of the original cost. While I don’t see myself ever making tutorials again, I hope that my website can remain a useful resource for years to come.

Footnotes

An archived copy of the site can be found here, courtesy of the Wayback Machine. In an interesting coincidence, the website went offline shortly after the Library of Juggling was created.↩︎

I use this term very loosely. The only money I’ve ever made from juggling was $20 for appearing at the end of this commercial.↩︎

Unfortunately this is the best that I can do, since I kept few historical records of the site’s content. I guess fifteen-year-old me didn’t believe in version control.↩︎

This was in fact the legendary “Orinoco” from the UK’s Tunbridge Wells Juggling Club, who was (is?) very active in the online juggling community.↩︎

These completely arbitrary difficulty values are actually used by Wikipedia. I am apparently considered a “reliable source” for juggling, much to my horror.↩︎

In his email he helpfully pointed out that it had taken him only an hour to compile the list, after I had initially explained that I “could never seem to find the time”.↩︎

I’m not joking. Unicyclers, remember to tie your shoelaces.↩︎

You can use HTTPS by setting up a load balancer on GCP, but that is ~10x the cost.↩︎

I had originally achieved something like this by using template files in Macromedia Dreamweaver 8. Make of that what you will.↩︎